History of the Camino de Santiago

To understand the history of the Camino de Santiago, we must journey back many centuries to the evangelizing tradition of one of the twelve apostles of Jesus, St. James the Greater, in the lands of Roman Hispania.

After the death of Jesus, James became an integral part of the early Church in Jerusalem. He was assigned the territory of Hispania for his evangelizing work. However, James had to return to Jerusalem when called to accompany the Virgin Mary on her deathbed. It was there that he faced torture and was ultimately beheaded in the year 42 by Herod Agrippa I, king of Judea, for defying orders not to preach Christianity.

The Remains of Saint James the Apostle

Legend has it that the disciples Athanasius and Theodore, after escaping taking advantage of the darkness of the night, stole the body of St. James the Apostle and took it in a boat to Gallaecia (Galicia). A journey that took them to Finis Terrae (today’s Finisterre) and later to the port of Iria Flavia (near today’s Padrón).

The tradition persists with the remarkable journey of the body of Santiago, which is transported in a cart pulled by oxen to the forest of Libredón. However, upon reaching this location, the oxen refused to proceed. Interpreting this as a divine sign, the disciples selected it as the final resting place for the remains.

Discovery of the Tomb of Saint James the Apostle

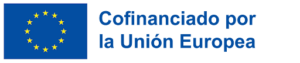

Eight hundred years later, the hermit Pelayo observed some glowing lights coming out of a nearby field, which would later be known as Campus Stellae (Field of Stars, nowadays Compostela). He immediately reported the discovery to Theodomyrus, bishop of Iria Flavia, who rushed to meet him. An altar with three funerary monuments was found there. One of them kept inside a beheaded body with the head under the arm. Next to it, a sign read, “Here lies James, son of Zebedee and Salome”. Thus, the remains were attributed to the Apostle James and his two disciples.

After being informed of the discovery, King Alfonso II The Chaste, ordered to build a small chapel over the remains of the sepulchre; a sacred place that underwent many remodelling until it became the current Cathedral of Santiago.

The ancient history of the Camino de Santiago: The Rise of Pilgrimages

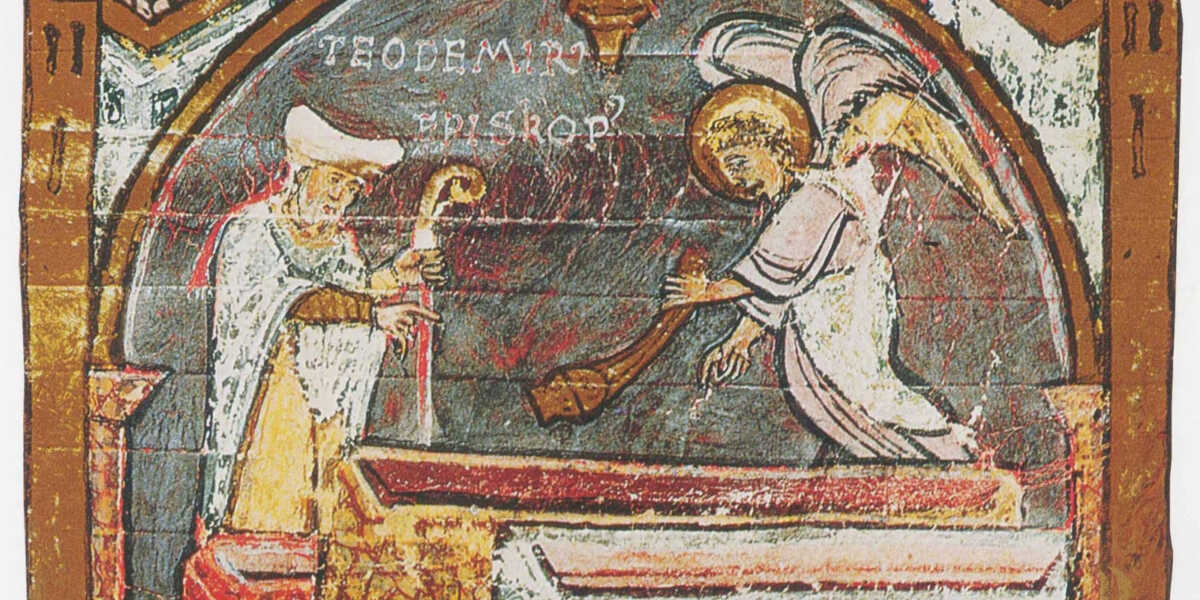

The news of the discovery of the apostle’s tomb spreads rapidly, transforming it into a pilgrimage site for millions of Europeans during the Middle Ages. The influx of pilgrims was so significant that hospitals, churches, and numerous inns were constructed along the Camino to provide shelter for the devotees.

Many historians and scholars of the Camino de Santiago will agree that the Jacobean routes, and especially the French one, contributed greatly to the dissemination of all the heritage and knowledge in the Middle Ages. The Camino de Santiago became, thanks to the constant transit of thousands of pilgrims, an information highway; a sort of medieval internet where knowledge and innovation were shared. Roads, bridges, hospitals and, of course, churches and cathedrals were built at the foot of the route to provide support and basic spiritual logistics to the pilgrims. Master builders, stonemasons and even the “camineros” mentioned in Chapter V of Book V of the Codex Calixtinus were essential for the construction of all this infrastructure.

Thus, at the beginning of the 11th century and as the Reconquest progressed, the most popular route was the one that began in Roncesvalles; known today as the French Way.

The pilgrimage became even more popular when the monk Aymeric Picaud created the Codex Calixtinus, an early travel guide detailing the stages of the French Way, accommodation, monuments, churches etc.. As time went by, new routes of the Camino de Santiago began to emerge from different parts of the peninsula and Europe. In this way the Camino de Santiago became the most important religious, commercial and cultural route in Europe.

But not all times were glorious for the Camino de Santiago. In the last centuries of the Middle Ages, pilgrimages to Santiago de Compostela experienced a great decline. The European wars, the Black Death and the Schism in the Christian world in 1378 caused the number of pilgrims to decrease considerably.

From the 16th century onwards, the number of pilgrims continued to decrease until it practically disappeared after the disentailment of Mendizábal, which meant the extinction of the hospitality of the monasteries that had been practised until then.

Resurgence of the Camino de Santiago in History

It was not until the mid-twentieth century when various initiatives began to emerge aimed at recovering the Camino from oblivion. Thanks to a new interest of the administrations, the visits of the Pope to Santiago in the 80s, the emergence of multiple associations and brotherhoods and the declaration of World Heritage of Humanity in 1987, the Camino de Santiago rose from decadence to become the most important pilgrimage in the western world.

We cannot overlook the role of one of the key proponents in revitalizing modern pilgrimages along the French Way: the parish priest of O Cebreiro, Elías Valiña. He was largely responsible for much of the symbolism associated with the new era of the Camino de Santiago, notably the iconic yellow arrow.

At the end of the 70s, Elías began to mark the French Way with yellow arrows, the current symbol of the Jacobean route. An anecdote about the parish priest in the Pyrenees became very famous. After the Guardia Civil stopped him with a pot of yellow paint in his hand drawing the striking arrows, they asked him what he was doing. His answer was “Preparing a great invasion from France”, with which he became a visionary.

Skip to content

Skip to content