When discussing the Camino de Santiago and its history, it is essential to mention the Codex Calixtinus, a gateway to the Camino de Santiago and the rich Jacobean culture of the Middle Ages. This work, which combines miracles, history, and a detailed pilgrim guide, has left a profound mark on the tradition of pilgrimage. Carefully preserved in the Cathedral of Santiago, it is a fundamental piece for understanding the Camino de Santiago during medieval times. Ready to uncover its fascinating history?

What is the Codex Calixtinus?

The Codex Calixtinus is a manuscript dating back to the mid-12th century, of great significance to Jacobean culture and, more broadly, to the historical trajectory of the Late Middle Ages. Written in Latin, the original copy is kept in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, although there are several later copies scattered across different countries.

Front and back cover of the Codex Calixtinus

Its creation was driven by the Church of Compostela during the time of Archbishop Diego Gelmírez (1068–1140), whose sole aim was to solidify Compostela’s significance as an apostolic seat and pilgrimage center—in essence, to establish Santiago as a major hub of Christianity, akin to Rome and Jerusalem.

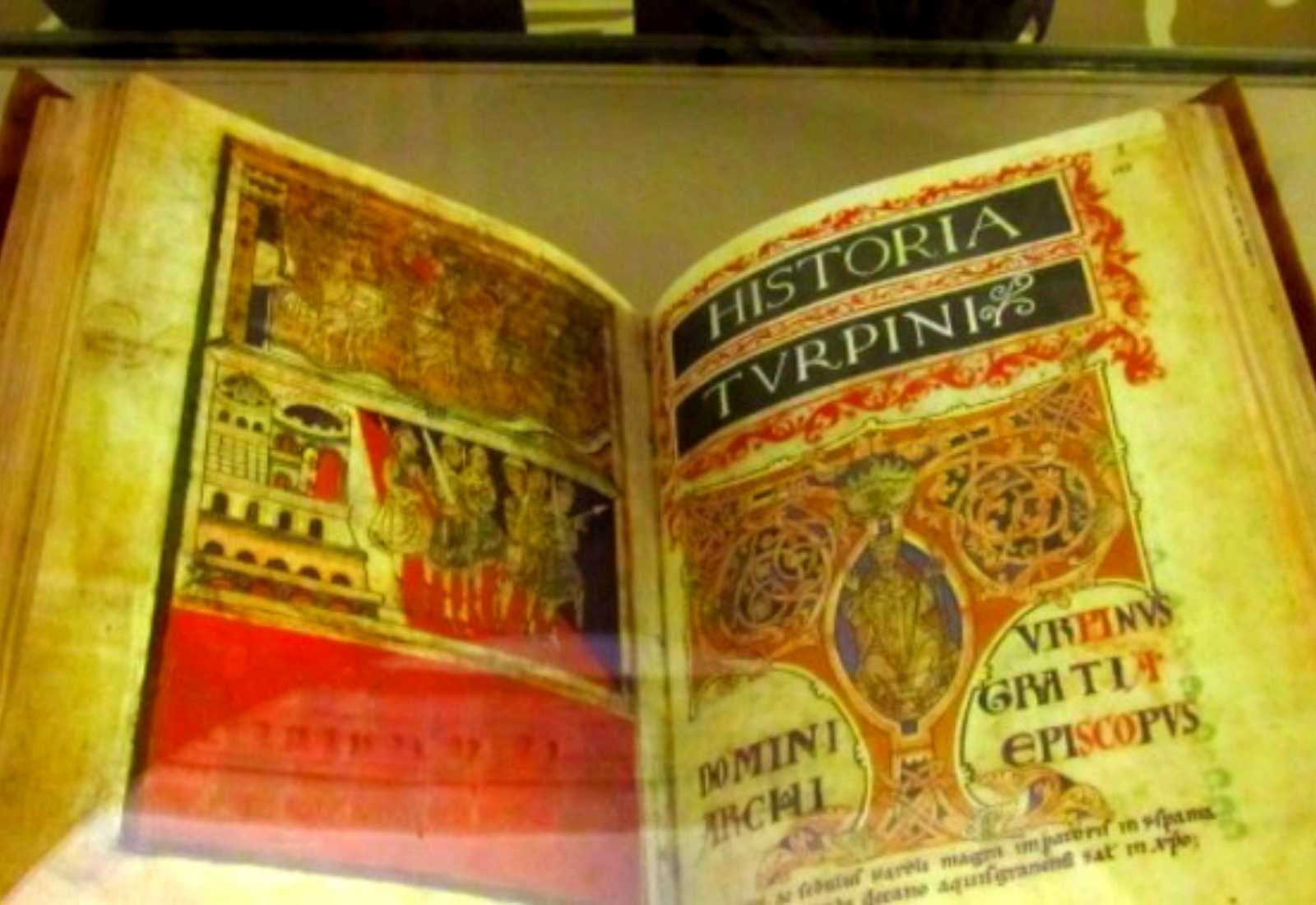

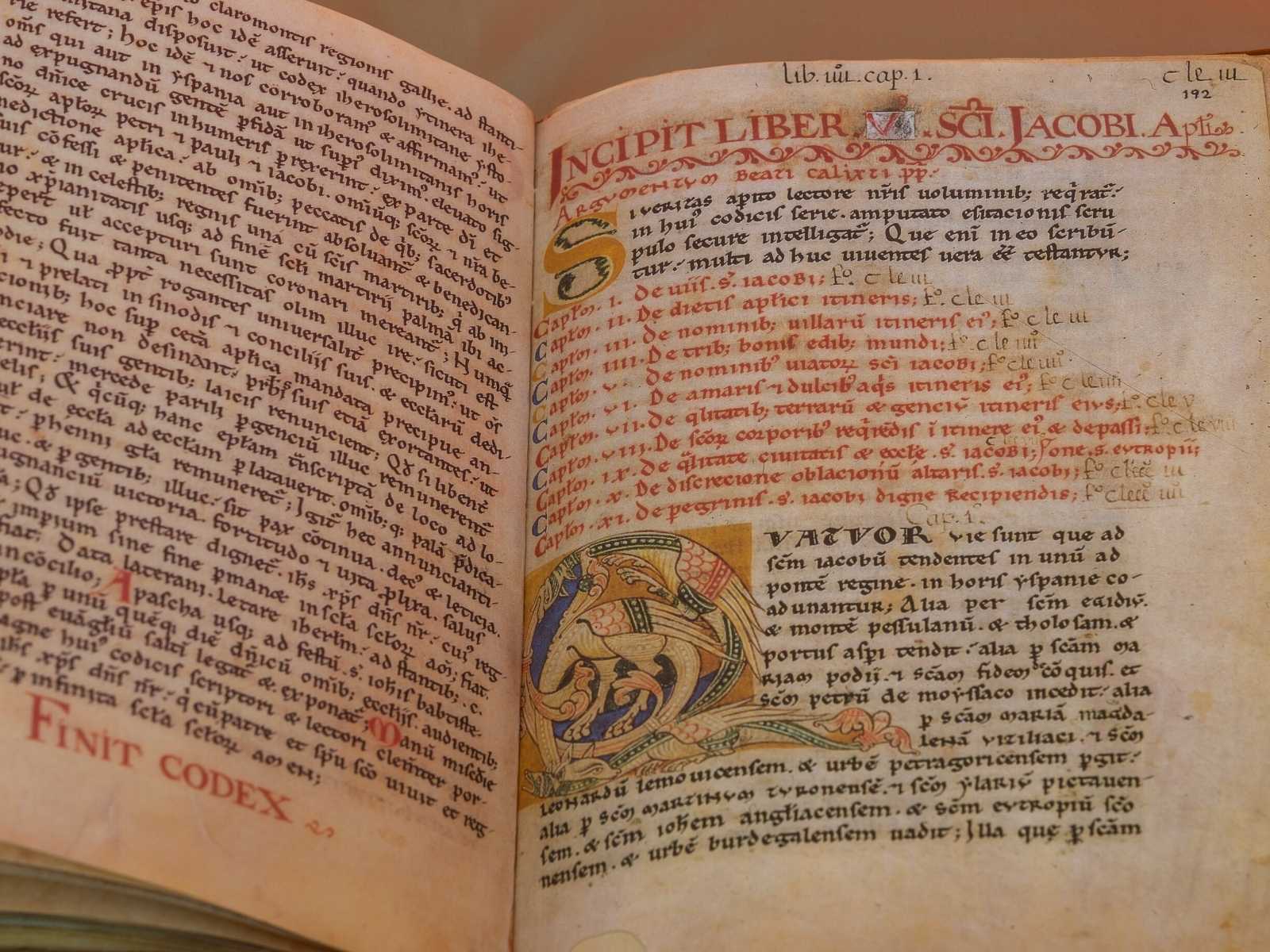

Sections of the Codex Calixtinus

The Codex Calixtinus is an extensive text divided into five books: liturgical texts related to the Apostle James, miracles attributed to him, the events surrounding the Traslatio (the journey of the Apostle’s remains to Galician lands), Charlemagne’s presence in Hispania to liberate the routes to Compostela from Muslim control, and the pilgrim’s guide from France to Santiago. Additional miracle accounts, musical compositions, and texts justifying the work further enrich this compendium of Jacobean culture.

Attributed in its entirety to one or perhaps several anonymous authors, Book V—the one most relevant as a guide for the medieval pilgrim—is generally credited by experts to the French monk Aymeric Picaud. Historically, the Church of Compostela associated the authorship with the Cluniac Pope Calixtus II (c. 1050–1124), hence the work’s title. However, this attribution may have been intended to legitimize and lend authority to the book and to Santiago itself as an apostolic seat. While this pontiff is presented as the author of the first and longest book and part of the second, most experts consider this claim to be false.

The Codex Calixtinus, the first guide to the Camino de Santiago, may be the work of multiple authors

This work has been referred to in various ways, depending on the specific copy in question. The original, preserved in the Compostela basilica, is known as the Codex Calixtinus. The French philologist and writer Joseph Bédier (1864–1938) coined the term Liber Sancti Iacobi to refer to the complete (or nearly complete) copies that are preserved in different locations around the world. Other authors have proposed additional names, such as Iacobus, suggested by medievalist Manuel Cecilio Díaz y Díaz (1924–2008), specifically for the first and second books, as the codex opens with the following text: “Ex re signatur, Iacobus liber iste uocatur” (“Rightly named, this book is called Santiago”). The French writer Pierre David, on the other hand, refers to the text as Codex Compostellanus or Liber Calixtinus.

It is not the medieval text of greatest artistic value, but its miniatures provide highly valuable information. Its illuminated capitals (the large, richly decorated, and colorful initials at the start of a paragraph) are the most notable aspect in terms of the codex’s aesthetics. According to researchers, various theologians, scribes, writers, poets, and other artists likely traveled to Compostela from France under the initiative of Archbishop Gelmírez.

Illustrated images of the Codex Calixtinus

Why is the Codex Calixtinus so important?

Of particular interest to us is Book V, commonly known as the guide for pilgrims, a genuine travel guide to the French Camino de Santiago. This Liber peregrinationis, composed of an introduction and eleven chapters, is a detailed and precise guide describing the various French routes leading to the French Way in Spain, as well as the route itself through the Iberian Peninsula.

It provides information about the towns along the way, their churches and buildings, the quality of their waters, rivers, and lands, the relics encountered, and more. It even acknowledges and pays tribute to all those who worked on the construction and maintenance of the Camino’s infrastructure. Chapter VII is particularly striking, offering descriptions of the people living in the towns along the route. For example, Galicians are described as “irascible and very argumentative.”

If its author or authors were alive today, they would undoubtedly be worthy candidates for the Nobel Prize in Literature. In fact, this literary monument has been recognized by UNESCO as part of the “Memory of the World Register” due to its historical significance.

The Theft of the Codex Calixtinus

Such is its value that, on July 5, 2011, the medievalist at the Santiago Cathedral Archive discovered that the work was missing from its safe. The police were alerted, and an investigation began that bore fruit a year later: the codex was found wrapped in cloth and amidst garbage in the garage of José Manuel Fernández Castiñeiras, an electrician who had worked for 25 years maintaining the Santiago Cathedral and had access to the book. For the theft of the Codex, he was sentenced to 8 years and 2 months in prison, although he was released in 2019 for medical reasons.

The Museum of the Cathedral of Santiago

Published in 2016 by Alvarellos Editora, you can find a copy of Book V of the Codex Calixtinus at any bookstore. Without a doubt, it’s one of the must-read books about the Camino de Santiago that every pilgrim should know. Plus, it’s a short and very enjoyable read—100% recommended! And if you’re inspired to walk a route of the Camino de Santiago, we can offer you our very own 21st-century guide to the Camino.

Skip to content

Skip to content

Leave A Comment